New Facebook privacy tip: 'Super-logoff'

- Some Facebook users deactivate their accounts instead of just logging off

- They then reactivate the account -- with all info maintained -- to log on again

- Report: Young people more likely than older counterparts to alter Facebook settings

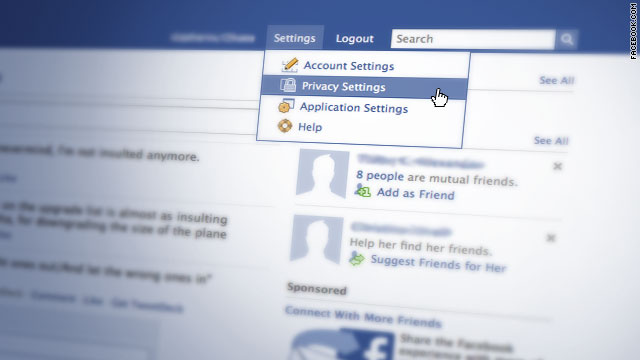

(CNN) -- If clamping down the privacy settings on your Facebook page isn't enough to help you sleep at night, take a cue from the youth of America.

Try the "super-logoff."

Performing the trick doesn't take superhuman powers. Instead of just closing a browser window or clicking the "log off" button at the top right of the Facebook homepage, some young, privacy-concerned users are simply deactivating their Facebook accounts each time they leave the site.

Then they reactivate their accounts to log back on.

Why go to all this trouble?

Well, for one, it's not hard. Facebook makes it notoriously difficult to fully "delete" an account. But "deactivating" an account is easy -- it only takes a single click, and deactivated Facebook users maintain all of their friend connections, wall posts, photos and the like. The upside, for the privacy paranoid, is that when a "deactivated" user isn't on Facebook, no one else can see their profile, post on their wall or tag them in photos.

For privacy-minded people, it's a soothing alternative. It gives them ultimate control.

Microsoft researcher and social media expert danah boyd (she doesn't capitalize her name), who identified the trend this week on her blog, believes young people may have good reasons for deactivating and reactivating their accounts frequently.

"In many ways, deactivation is a way of not letting the digital body stick around when the person is not present," boyd writes in a November 8 post.

"This is a great risk reduction strategy if you're worried about people who might look and misinterpret. Or people who might post something that would get you into trouble."

She credits Michael Ducker, a program manager at Microsoft, with inventing the "super-logoff" term.

As part of her field work, boyd has spoken with kids who use the technique to maintain control of their pages. One person she mentions on her blog, Mikalah, "wants to be a part of Facebook when it makes sense and not risk the possibility that people will be snooping when she's not around."

The blog All Facebook adds that this practice is fundamentally different, and in some ways simpler, than changing your privacy settings on the site:

"Notice that, while you or I might think that spending five minutes setting your privacy settings correctly might solve the hassle of having to deactivate your account when you log out, in reality these are two actions that accomplish different things," Jorge Cino writes on that Facebook-focused blog.

"Mikalah and others like her want their friends to post stuff on their wall or tag them in a photo, but they don't want them doing it when they're not there to make sure it's okay. Most importantly, someone like Mikalah doesn't want any friends of friends digging up her profile when she's not 'around.' Deactivating her page literally erases her from Facebook. She becomes untraceable."

Others don't go quite as far, says boyd. Instead of deactivating her account, Shamika engages in practice known as "whitewalling," boyd says. She deletes every "like," comment and photo almost immediately after it's posted.

"When I asked her why she was deleting this content, she looked at me incredulously and told me 'too much drama,' " boyd writes.

She continues:

"Pushing further, she talked about how people were nosy and it was too easy to get into trouble for the things you wrote a while back that you couldn't even remember posting let alone remember what it was all about. It was better to keep everything clean and in the moment. If it's relevant now, it belongs on Facebook, but the old stuff is no longer relevant so it doesn't belong on Facebook.

"Her narrative has nothing to do with adults or with Facebook as a data retention agent. She's concerned about how her postings will get her into unexpected trouble with her peers in an environment where saying the wrong thing always results in a fight."

These stories add interesting nuance to the debate over young people and privacy on the Internet. The general line of thinking -- which is backed up by some surveys -- is that young people care less about online privacy than older people.

A Forrester Research study released this week, for example, found that fewer members of Generation Y say they are "very concerned" about social network privacy than Baby Boomers.

But there appears to be more going on.

A Pew Internet report, released on May 26, found young people are more likely than their older counterparts to alter their Facebook settings and to actively manage their online identities.

From that report:

"Young adults are the most active online reputation managers in several dimensions. When compared with older users, they more often customize what they share and whom they share it with."

This suggests younger people do care about their privacy and reputation online and will take steps -- sometimes big ones, as boyd's blog post shows -- to manage these increasingly important digital identities.

What do you think of these practices? If you use the "super-logoff," or plan to try it, let us know in the comments section below.

http://edition.cnn.com/2010/TECH/social.media/11/12/facebook.superlogoff/index.html?iref=obinsite

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar